There’s been an increasing focus on mental health during the past few years and not without good reason:

- Within the UK, one in four people is likely to experience a mental health problem each year in England alone.

- One in six people will experience depression, anxiety or a combination of the two. 1

The impact of these mental health problems can be crippling, with the adverse effects impacting upon every aspect of daily life.

So if you’re reading this and think you may be experiencing depression or anxiety, then it’s important that you reach out for support as soon as possible. Even just telling one person how you feel can help. When we open up about how we’re feeling it becomes much easier to tackle the problems we’re experiencing.

If your sleep is a problem, then we can help.

Sleep can be significantly affected by depression and poor sleep can cause us to feel low. As we know from the scientific literature, a good night’s sleep benefits health, mental ability and mood.

Depression can affect sleep and sleep can affect depression

To give you a full review of how depression and sleep interact with each other would fill a book. Instead, we’ve broken down the key scientific findings to show how people living with depression and poor sleep can use what we’ve learned about these interactions to improve their mood and achieve better sleep.

Does depression cause an unusual sleep pattern or does an unusual sleep pattern cause depression?

Many people with depression experience poor sleep, either in the form of sleeping too little or too much. In fact, when people seek treatment for poor sleep, many of them also have symptoms consistent with depression. 2

Conversely, people seeking treatment for depression will often complain of poor sleep. 3 ‘Poor sleep’ can include:

- taking a long time to fall asleep

- waking up frequently during the night

- lying awake in bed for a long time during the night

- no feeling refreshed after sleep.

These symptoms can affect our mood, make it difficult to concentrate, leave us feeling lethargic and lead to daytime tiredness that people living with depression are all too familiar with. 2

Even though the sleep that those with depression experience is poor, it’s not accurate to say that depression causes a lack of sleep. In fact, many people living with depression experience hypersomnia — the condition of sleeping too much.

However, if that sleep is of poor quality then it will affect how the person feels and functions the next day.

It’s also a sad fact that a link has been observed between extremes of sleep time and suicide risk but this may not be directly attributable to depression. 4

At this point, it’s worth asking ‘why does depression affect sleep?’

The REM theory of sleep — and why it’s not quite right

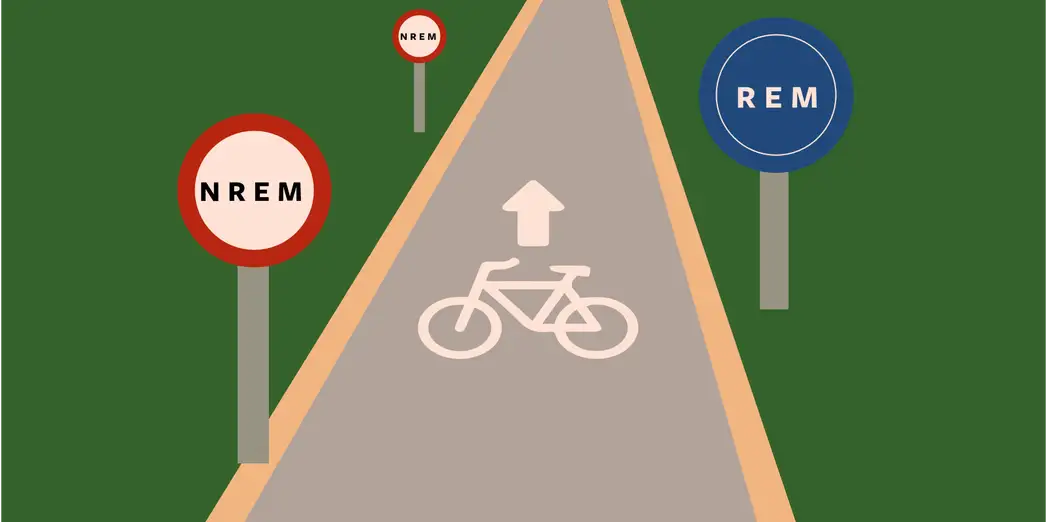

Sleep consists of a number of stages, one of which is termed REM (rapid eye movement) sleep. The REM stage of sleep is linked to dreaming and during this stage our brain activity levels are similar to what they are when we’re awake.

There are also non-REM (NREM) sleep stages, with the the most important of these being NREM slow-wave sleep. That’s the type of sleep we need to feel refreshed in the morning.

During sleep, we alternate between REM and NREM stages and it’s been found that people living with depression spend a greater amount of their sleep time in the REM stages. 5 6 7

This has led to the suggestion that increased REM sleep leads to depression. This is something you may have read online or in earlier scientific literature relating to sleep science and depression but it isn’t strictly true.

Mistimed REM sleep is linked to depression

A more helpful way to understand the sleep disturbances that people with depression experience is to think of their sleep cycle as being somewhat ‘shifted’.

As a result of this ‘shift’ REM sleep appears to be experienced earlier in the night and consequently, the sleeper gets less restorative slow-wave sleep during their time in bed.

The disruption to the timing of REM sleep appears to lead to mood disturbances like depression because it reduces their opportunity to get that restorative slow-wave sleep.

Now that we’ve explained a little about how sleep and depression are linked, let’s consider what options there are for someone living with depression to improve their sleep.

Antidepressant treatment

Antidepressants are commonly used as a first line of treatment for depression. There are many types of antidepressants but the most commonly prescribed today are in the SSRI class — selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

SSRIs are usually the first choice medication for depression because they generally have fewer side effects than most other types of antidepressant.

Although the mode of action of most antidepressants isn’t completely clear, one thing that most of them seem to do is to reduce REM sleep. 8

A notable exception is the antidepressant agomelatine. It doesn’t do anything to the amount of time spent in REM sleep but does appear to increase the amount of slow-wave sleep a person gets — along with re-aligning the ‘shifted’ sleep cycle observed in people with depression. 9

What this tells us is that suppression of REM sleep isn’t necessary for an antidepressant to work. It’s just that a lot of antidepressants on the market happen to suppress REM sleep.

Because of this effect, when a person first starts taking antidepressants their sleep may become more disturbed to begin with. After a few weeks most people start to experience improvements in their mood as well as their sleep.

As the antidepressants work to reduce the severity of depressive symptoms, this should lead to an increased sense of wellbeing and overall improvement in quality of life.

Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi)

CBTi is a specific form of therapy that is very effective for insomnia and it has been found to have a positive effect on mood as well as sleep. This makes sense, as when we sleep better we tend to feel better. 10

Data from our own research demonstrates that CBTi can help with depression. A large percentage of people (around half) who we help to overcome poor sleep also report an improvement in their mood.

People also report reduced depressive symptoms following support from Sleepstation even though we didn’t provided any direct treatment for their depression.

We believe that’s because of the unique way in which we deliver remote CBTi. One service we provide through our digital sleep clinic is our Sleep Transformation Programme, a fully supported CBTi course, delivered entirely online but highly personalised to the individual and supported by our dedicated team made up of highly-trained sleep coaches, therapists and sleep experts.

We work with people to understand what’s going wrong with their sleep so that we can help them to tailor the sleep science to their individual needs and circumstances.

We believe that this uniquely personalised approach is what makes Sleepstation so effective.

Some components of CBTi can target depression

Most CBTi courses, ours included, will recommend some form of sleep rescheduling, which usually involves setting a fixed getting up time and reducing the time spent in bed for a short period.

This approach is called sleep restriction therapy but it’s badly named as the intention is not to restrict the amount of sleep that a person gets — rather to consolidate their sleep and restrict the time they spend in bed awake.

Sleep restriction therapy usually results in mild sleep deprivation in the early stages. This can lead to an increase in slow-wave sleep which may be what’s driving the mood improvements that have been observed in some people with depression when they complete a course of CBTi. 11 12

Of course, prolonged sleep deprivation to lift mood is unsustainable but the science does suggest that sleep restriction can be an effective, short-term, non-drug approach that can complement any antidepressant medication a person may be taking.

In summary

- Depressive symptoms are commonly observed in people with insomnia and insomnia symptoms are commonly observed in those with depression.

- Treatments can include — but aren’t limited to — antidepressant therapy and some components of CBTi.

- A well designed and supported course of CBTi may improve symptoms of both insomnia and depression.

If you’re experiencing depression and associated sleep problems, it’s important to reach out for help.

At Sleepstation we’re not specialists in depression but we can, alongside a dedicated mental health caregiver, give you the best chance possible to get your insomnia and mood under control.

References

- How common are mental health problems? [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: http://mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/statistics-and-facts-about-mental-health/how-common-are-mental-health-problems

↩︎ - Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Lemoine P. Comorbidity of mental and insomnia disorders in the general population. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(4):185–97. ↩︎

- Nowell PD, Buysse DJ. Treatment of insomnia in patients with mood disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14(1):7–18. ↩︎

- Gunnell D, Chang S-S, Tsai MK, Tsao CK, Wen CP. Sleep and suicide: an analysis of a cohort of 394,000 Taiwanese adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(9):1457–65. ↩︎

- Riemann D, Berger M, Voderholzer U. Sleep and depression–results from psychobiological studies: an overview. Biol Psychol. 2001;57(1–3):67–103. ↩︎

- Van den Hoofdakker RH, Beersma DG. On the contribution of sleep wake physiology to the explanation and the treatment of depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1988;341:53–71. ↩︎

- Moretto U, Palagini L. Sleep in Major Depression. In: Handbook of Sleep Research. Elsevier; 2019. p. 693–706. ↩︎

- Wilson S, Argyropoulos S. Antidepressants and sleep: A qualitative review of the literature. Drugs. 2005;65(7):927–47. ↩︎

- Eser D, Baghai TC, Möller H-J. Agomelatine: The evidence for its place in the treatment of depression. Core Evid. 2010;4:171–9. ↩︎

- Cunningham JEA, Shapiro CM. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) to treat depression: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2018;106:1–12. ↩︎

- Berger M, van Calker D, Riemann D. Sleep and manipulations of the sleep-wake rhythm in depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2003;(418):83–91. ↩︎

- Wirz-Justice A, Van den Hoofdakker RH. Sleep deprivation in depression: what do we know, where do we go? Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(4):445–53. ↩︎